14.02.2021 - 10 min read

A story from Elliott Russell on what it takes to make it happen in the midst of a pandemic.

At the beginning of December I am sat in The Rising Sun pub in London Bridge. Sat opposite me is my good friend Daniel Emo. Some people know him as Dan, others simply as Name, having officially changed his name to Name Surname back in 2016 for a project at the Royal College of Art. To me and others who know him from our home city of Portsmouth he is, and always will be, Emo. The pubs are inhaling their final breath of customers before they bolt their doors shut for the foreseeable future due to the pandemic; at that point only allowing you to drink pints if you order some food. In the corner a solemn local sits pint in hand amongst a vast semi-circle of his empty glasses, a slumped pagan praying to his standing stones. In the centre of his glass altarpiece sits a solitary untouched pork pie on a small china plate. This meat ticket into the boozer is the ace of spades up his sleeve; the talisman that shields him from the virus.

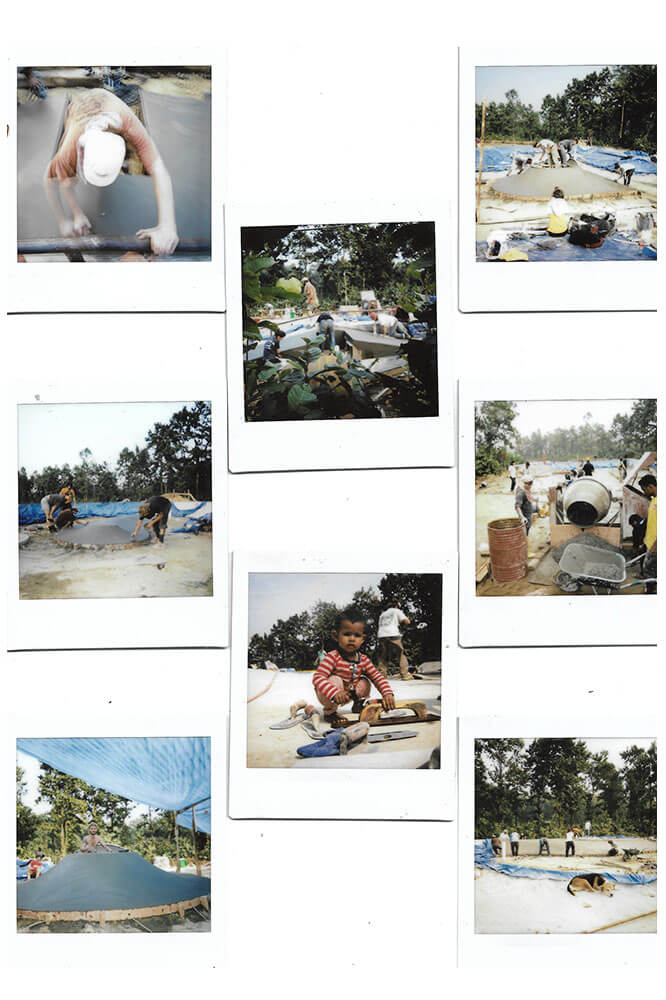

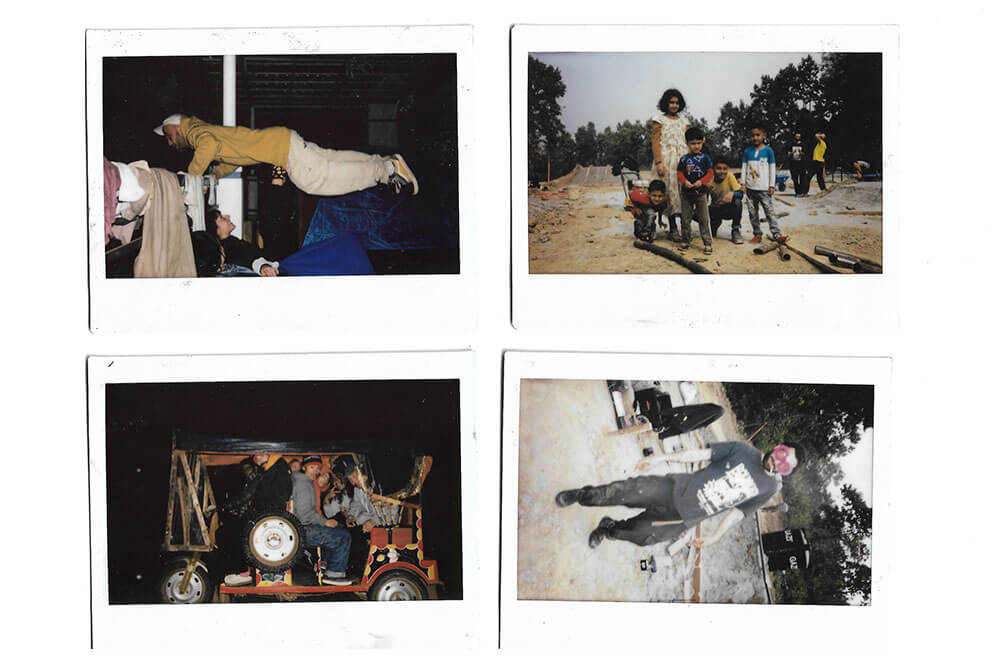

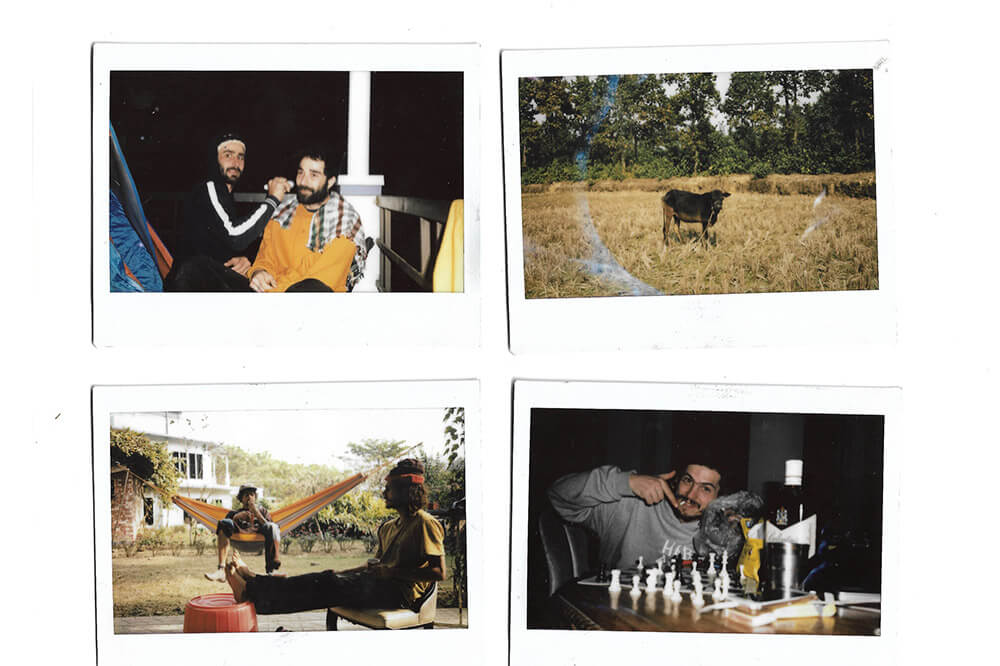

Polaroids from Léo Poulet

The purpose of our meeting is for slightly sombre reasons, fresh heartache for me, healing heartache for him. My head feels like two drunk men playing Jenga, I need the stability and soothing temperament of an old friend like Emo to chew our problems down to the bone with. Our plate of scampi sits idly on the table while we swap advice over a few beers and the chat inevitably swings towards travel, pressing that ejector seat button. After listening to me ramble about Spain for a time, he takes a sip of lager, sits back and, with a knowing raise of the eyebrows, offers up his curveball.

“I’m going to Bangladesh in January to build a skatepark.”

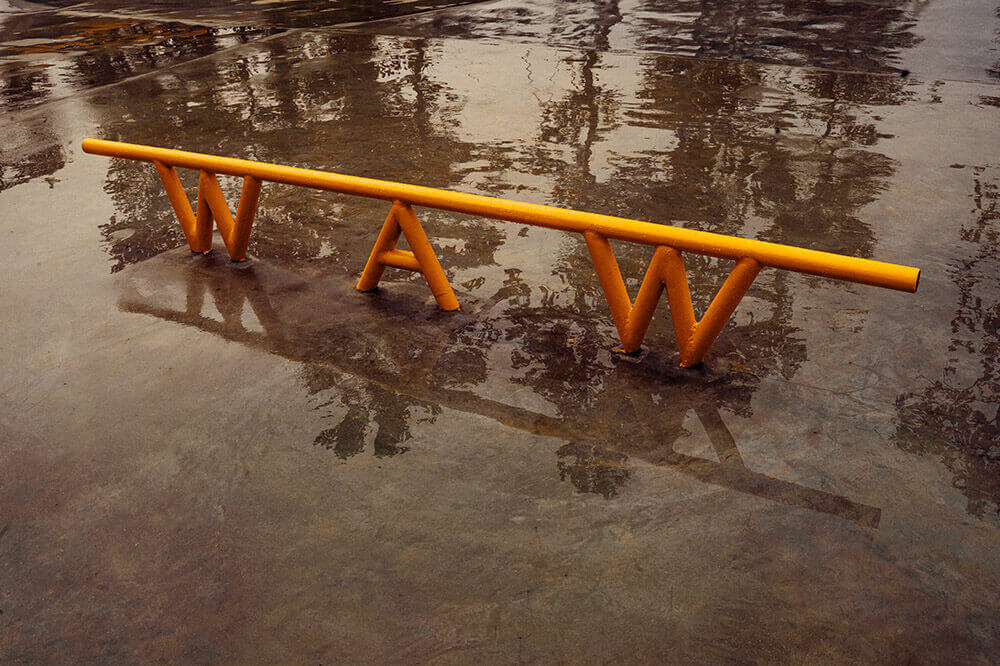

I was aware that he had been involved with the guys at WAW for a while, going to Morocco in 2017 to build a skatepark there with MLSL to aid a budding skate scene, and the idea had always got me stoked. Dicing together three of my favourite things to do in life, building, skateboarding and travelling the world, all while doing something genuinely life changing for underprivileged kids, young people and anybody that wants to ride a skateboard that doesn’t have the space to do so, bringing that feeling that I completely identify my own childhood and adolescence with to others, I cannot think of anything better to do with my time. A carpenter by trade but currently without a vehicle, I had the beginnings of a van fund in my bank account. That was the plan, but I figured a plane ticket to Bangladesh was a far better use of money. There will always be vans.

“Can I come with you please?” I asked.

One month later we were on our way to Dhaka via Istanbul.

Polaroids from Léo Poulet

Getting there was obviously not without its difficulties given the current worldwide situation, at the time the United Kingdom was on the brink of another full lockdown which would seemingly last through the winter and possibly into the spring. The official story we’d need to get a tourist visa, a work visa being too long-winded, was that we were travelling to Bangladesh on vacation to visit our good friend Susie. We wanted to hang with her and her friends and enjoy the nature. Also that BSKA (Bangladesh Street Kids Aid) were hosting a sports event, and it’s an event that we’d really love to join.

After handing over our passports and a large amount of paperwork through an open bay window at the Bangladesh High Commission in South Kensington, we had to figure out the vaccines and the mandatory Covid tests. With Emo holed up down in Portsmouth, I was still travelling from London to Kent each day for work, praying that I didn’t contract the virus before the 17th of January. The date approached and we took our tests within the 72 hour window before the flight and nervously waited for the results, both coming back negative; one source of anxiety stamped out. The next obstacle was leaving the country when we weren’t allowed to. Although we were technically allowed to leave the UK for work, our visas had etched into them, “WORK PROHIBITED. PAID OR UNPAID.”

“Hello gentleman, why are you travelling to Bangladesh?”

“For work, officer.”

“Well then why do these clearly state that they are tourist visas?”

“Errrr.”

Checkmate.

Polaroids from Léo Poulet

What actually happened was, whilst checking in our hold luggage, a stoically glamorous Turkish Airlines attendant at the front desk looked over our passports and visas and got busy attacking her computer. Pursed red lips and the sound of fresh nail polish hammering the keyboard furiously bullying the information out of it. She finally looked up and went to hand them back, but just before she loosened her grip, the passports clamped in those gleaming scarlet talons, she faced Emo and, looking over her eyebrows, said, “These are working visas, yes?”

Emo then proceeded to display a curious cocktail of sound and expression that I don’t believe I’ve heard or seen before. Imagine a mixture of a yes and a whimper, passing by way of a sigh, with a long tail, trailing off into an awkward silence, all with startled look on his face that said both “Of course” and “Pardon me?”

Confused yet satisfied with Emo’s puzzling response to her question, an uninvited smile briefly crept onto her stony face and she released her grip on the passports. Another big checkpoint reached.

Polaroids from Léo Poulet

Many hours passed, lubricated with airport whiskey, a brief stop in Istanbul, a beer sat in a fake indoor cobbled plaza, a security lady who erratically dissected my entire bag, seemingly just to see the look on my face. In the queue for the Dhaka flight we saw two dudes who looked like they were skateboarders and we wondered if they were headed our way. We heard them mention Gazipur, where we were headed for the build. When we landed in Dhaka we were put into a small holding pen made from plastic sheets with forty or so other people in close proximity, everybody waiting to see about the quarantine situation. Negative Covid results clutched in our hands, we already had a guy waiting outside the airport ready to drive us to the site, the build having begun at the beginning of January. We were so hungry to get out. Growing tired, Emo turned to me and said, “Let’s get out of here, man. We’re not getting anywhere sat in here.” Following his lead, through a mixture of sheer luck and feigned authority, we ducked the guards at the front of the pen and were out with the rest of the passengers, surrounded nose to neck with a load of pissed off people waving their papers and fingers. This was the most people we’d been so close to in a while and were not keen to contract Covid this late in the game. With us nearly at the front of this new queue, the crowd’s anger and volume was growing intensely and I saw a plain-clothed young man up front swing his shotgun from behind his back and start carefully thumbing it. I stood there channeling some inner calm, embracing the chaos, enjoying that genius abandonment of all order that sometimes strikes unannounced in certain situations. It’s hard not to find it all amusing, stripped of all control, being pushed and pulled about as if in a mosh pit where the band playing is the Bangladeshi army. All you can do is tighten the belts on your straight jacket, pretend it’s an expensive coat, and keep shuffling forwards. But all the time I was also wondering how bad this would need to get before that young man up front with the half-smile contemplated taking aim at the crowd to dull the madness. We crawled along in that pissed-off gridlock to the end, finally received our “home quarantine” stamps and were on our way to the exit when the same guards clocked us and threw us straight back in the plastic cube. During this second time in the pen, furiously sanitising our hands every five minutes, constantly arranging myself on my orange plastic chair, arse cheeks like two clenched fists from all the sitting, I saw the same young man with the shotgun enter and make his way towards us. He was hunched over wheeling a small trolley, the shotgun standing to attention on its strap behind him, protruding quiver-like from between his shoulder blades. As he got closer he reached into a cardboard box on the trolley and pulled out two sealed party bags containing some water, a peanut bar, a muffin and a mango juice. I laughed about having entertained the idea of this same man pointing his shotgun at me only an hour earlier, now he was handing me a delicious mango juice. The world is hilarious. I smiled and gave him a thumbs up. He moved his head closer as if to hear it and smiled back.

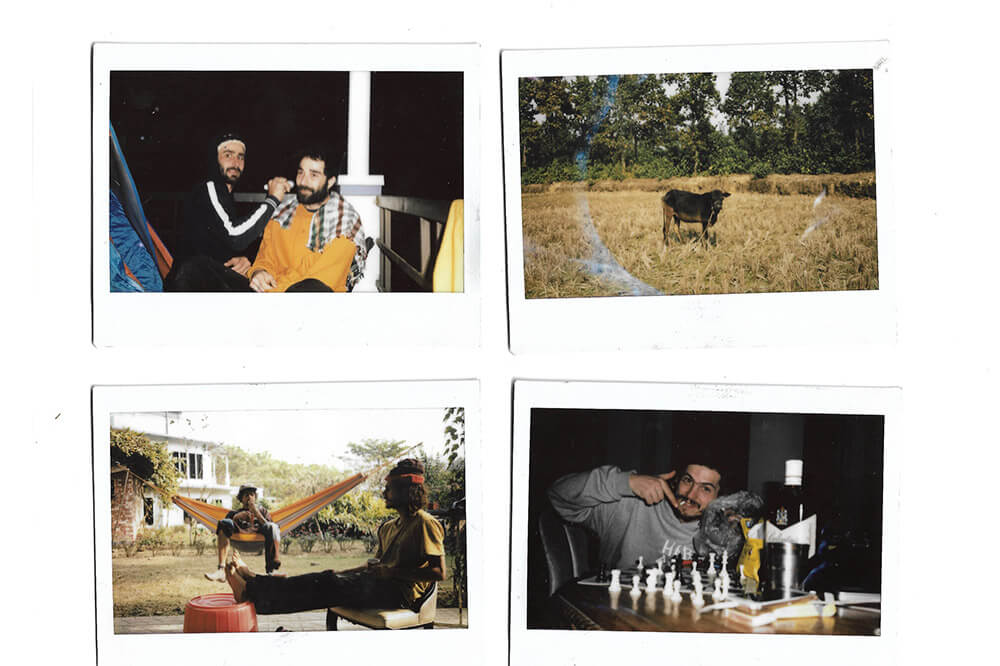

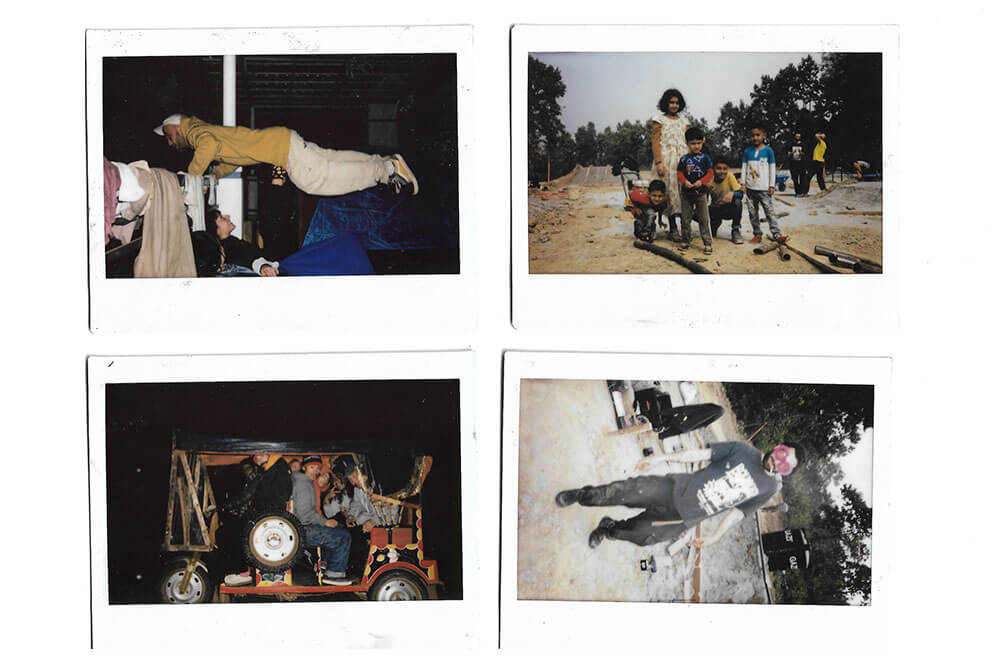

Polaroids by Elliott Auffray

A further two hours later a sea of young military personal in blue camo filled the latest area of the airport we were being held in. Close to the exit and in our final queue to get out, one soldier held a stack of confiscated passports taller than a toddler and ours were somewhere deep within it. We were at last told we’d need to quarantine in a government approved hotel for four days, with us being responsible for the cost of the stay. We’d then need to take another test and we’d be released, given the results were negative. If positive, we’d need to move to a hospital for fourteen days, again covering those costs ourselves. We were desperately flitting between various soldiers, trying enquire about this list of hotels, to home in on the cheapest available, but it was frustratingly hard to locate. It seemed to me that a common scene at that airport was to see a lot of men, both military and suited, stood chatting about how to resolve a situation, none of them really knowing what was going on. In a bid to combat the lack of insight from any of these talking men it seemed there needed to be at least three times as many of them, pacing around wildly, bouncing off of one another, losing each other for a while, finding each other again, the whole group of them whirling around, pulled by incomprehensible forces like loose marbles in the back of a pickup truck on a bumpy road.

Polaroids by Elliott Auffray

When we finally got our hands on the list we settled on a hotel called “The Monsoon Inn,” and I’m still not sure whether that was our decision or theirs, but at £20 per night including three meals a day from a set “quarantine menu” we couldn’t complain too much. Before leaving we decided it would be a good idea to confirm that our passports were in fact in that fat stack. We needed a solid visual, a promising look in the eyes from somebody important in a crisp suit and a badge, a signed piece of paper maybe, or a firm handshake, something more than a vague assumption that a random ocean blue soldier possessed them within his purple and green accordion. During this time we had the assistance of a small London-born Bangladeshi boy in our queue, chatting and translating for us, he was rad; the most helpful person in that airport by a country mile. Meanwhile the soldier rifled through the passport pile multiple times to no avail, an amateur camo-clad magician performing a bodged card trick with our identities, eventually roping in ten other meandering talking men to help in the classic airport style. At this a fellow passenger, who would also be staying at our hotel, turned to us and said, “How has this been for you guys?”

“It’s been one of the most complicated things I’ve ever been a part of,” I replied.

Another half an hour and we had our concrete visual. Able to very briefly hold our own passports, they were then snatched straight back and we were given a signed piece of paper promising to receive them back in four days. Finally we could leave. On the way out I asked a man that spoke fairly good English if he knew our hotel and what he thought of it. “Definitely nice,” was his response.

Polaroids by Elliott Auffray

The Monsoon Inn stood tall like a burnt match in the middle of the Tongi area of Dhaka, the lower floors being plush and habitable but each floor dwindling in completion as you ascended to the crumbling peek. The top floor contained within it an array of dusty once-chic furniture, open bags of cement, some old gym equipment and a room with neither an exterior wall nor a roof, providing an eight story drop panoramic view of Dhaka. One evening we gathered together a selection of found items in this gaping wound of a room along with our dinner to form an apocalyptic banquet scene; a metal frame with two rested pieces of wood formed the dining room table, a couple of threadbare purple velvet chairs headed each end with a central upturned iPhone for some torch candle light, all next to the sheer drop. The city sat throbbing below as we ate, trains raced by, shaking the floor beneath us while the horns of every single vehicle in Dhaka sounded at once, constantly announcing their presence. The buses rattled through the streets narrowly avoiding one another, sometimes not. They looked to me like stamped-on beer cans that, having been pulled back into forms reminiscent of the original shape, had received brilliantly colourful paint jobs to mask the dents. The intensity of the colours that ran through this beige city were unbelievable. As young children played badminton in bamboo courts, bats the size of eagles woke and soared through the buildings as the sun retreated back into that thick smog. The whole thing was like a film set, two dudes attempting to recreate an opulent scene in the middle of a building that seemed to have had the top bitten off. We were so bummed that we hadn’t managed to get straight to site, but relieved the journey was over for now, ending in one of the most surreal meals we’d ever had. As it got dark Emo turned to me from his end of our DIY restaurant and, over a mouthful of luke-warm curry, said, “It’s pretty cool really. Within twenty four hours you can be anywhere in the world. You just need to have one shit day.”

Picture by Heidi Facherson

Three days later, having explored every corner of the hotel, not being allowed out, we got the call to come down to reception for the Covid test. We wen’t down and Emo went first. Now, the image of him I have here is one that will hopefully be tattooed onto my retinas until I am old and grey. He’s sat nervous but upright as if proud on a grand red velvet wingback chair with shining gold trim, his bare feet in once-white, now-brown paper hotel slippers on the confusingly tiled foyer floor. His head is arched back, mouth open, as if looking at the moon in awe. A man in a hazmat suit leans over him, clamping down his tongue with a wooden stick and probing his tonsils vigorously with a swab. I guess you could say this isn’t an unusual scene nowadays, but Emo has a terrible gag reflex, so the image of his throat retching backwards and forwards like a baby bird being fed regurgitated food by its mother, all in that swanky red velvet chair. It’s a Polaroid I wish I owned.

Picture by Heidi Facherson

That same evening we were sat laying on our beds waiting for a call with the negative results we’d been waiting for. The phone finally rang, they were here and the concierge would deliver the news to our room. Half an hour went by and no knock at the door. Growing impatient, I ran downstairs to the reception to retrieve them myself. The man at the desk informed me that I’d just missed his colleague going up to our room so I excitedly climbed the stairs again back to our room to receive those golden tickets, the entry forms to the outside world. Our door stood open, a smart man blocking the way, in the background Emo sat on his bed holding a piece of paper with a drained expression on his face that made my heart sink through my stomach, fall out of my arsehole, slide down my trouser leg and roll across the floor.

“Positive, dude.”

“You’re joking, right?”

“Nope.”

He handed me the crumpled piece of paper; a list of names that looked like it had been scanned from an old computer screen, printed, photographed again with an old Nokia, then printed again from a toaster. Each name had a positive or negative next to them, ours both positive. He wouldn’t let us keep a copy of this sketchy document which I found odd. Disbelief is probably the reigning memory from that moment. We’d be missing the lion share of all the cool shit on site that we’d been getting hyped for. With the wrestling channel now muted on the hotel television, the evening that followed consisted of a lot of straight faced talking, rationalising, worrying, shrugging, backtracking, calculating, health assessing, tastebud testing, feigned nonchalance, a meticulous retracing of steps, forced reassurance, occasional outbursts of nervous laughter, all whilst imagining how much fucking money we’d have to spend on this fourteen day stay in a hospital. We poured two large whiskeys while we stewed, smoked a cigarette, drained the glasses and poured two more; taking it in turns to be the guy to say, “It is what it is man.” Having previously been starving, this news had killed our appetites, or it was the virus. The whiskey still tasted fine, so we poured a further two and called our mothers to tell them we’d be going to Bangladeshi hospital and not to worry.

Picture by Heidi Facherson

Already late, we decided to ring the reception first thing in the morning to try and wrangle staying in this hotel rather than a hospital. If that worked out cheaper then we’d far rather do that. One sketchy sleep for me, absolutely none for Emo, then I was back on the phone to our man downstairs at 7am. Before I had the chance to release our proposition he cut me off with, “Ah hello sir, I have good news this morning. You are both negative. Been a mistake. I’m coming to the room.”

I tried my hardest to maintain a straight face as Emo stood apprehensively studying the phone call. I calmly hung the phone on it’s hook, waited a moment, sighed, then delivered the news. Loud celebrating, a thudding hug, a window shattering high five and straight back on the phone to room service for some victory ice cream. The return of disbelief. After another undeservedly long wait a man delivered two far more official looking negative covid results to our room, both forms stamped with laboratory hallmarks, and we instantly fell asleep, the anxiety having finally dissipated.

Picture by Heidi Facherson

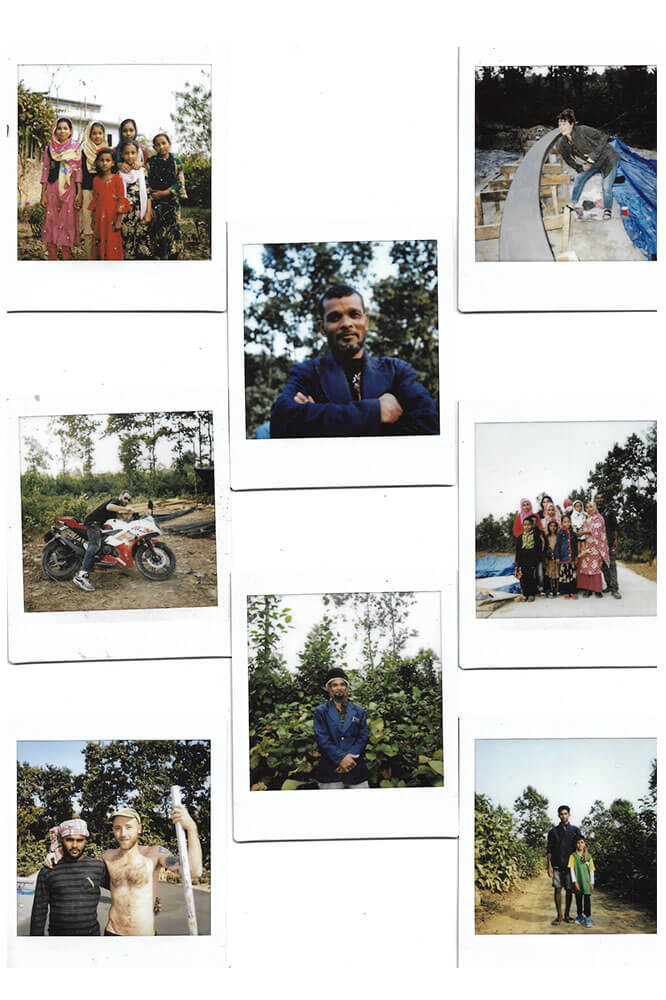

When we woke we reassembled our boards, collected our passports and were out of there, straight into a taxi on our way to the site. A £10 Uber got us all the way from the hotel down a two hour long hilariously chaotic road, eventually turning off into the dark forest, a few stops, U-turns, a phone call to Susie for help, then we were at the gate. I was apprehensive about meeting all the guys, Emo having met most of them already, but that soon vanished as the chatting started. Leo and Elliott sat talking, playing chess in the light of the patio, smoking cigarettes, stood up and welcomed us. “Aahhhh the English boys!!”

Picture by Heidi Facherson

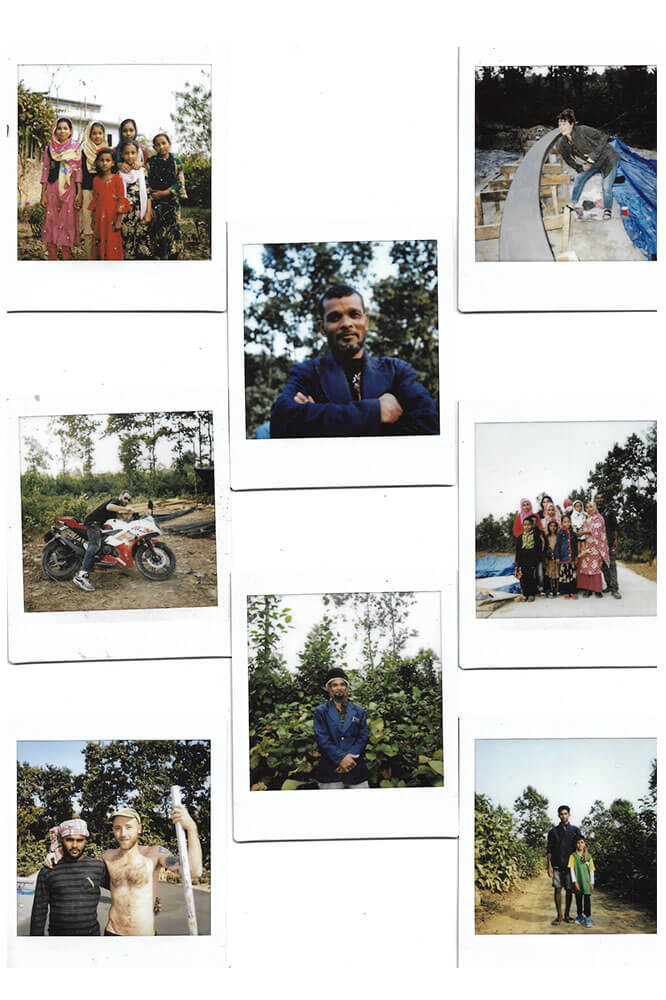

Gilbert raced out, embraced Emo, introduced himself to me and I was quickly made to feel at home. We were fed with ginger tea and showed to our room, an unfinished tiled bathroom, complete with mattresses, pillows, blankets and sleeping bags. I’d have been stoked with just a pillow so this was a solid set-up. Although knackered, we stayed up talking for a while, explaining to everybody the ride we’d been on. Sure enough the two dudes from the Dhaka flight, Marius and Sylvan, were there; having come from Switzerland they had dodged the four day hotel quarantine. The team was comprised of skateboarders from Denmark, France, Germany, Switzerland, America, Russia, Japan and England. I knew these builds were familiar work for the most, but I was completely in awe of these people, missioning from their various countries to the jungle in Gazipur, Bangladesh in the middle of a worldwide pandemic to build a vast swelling concrete structure to sew the seeds of skateboarding.

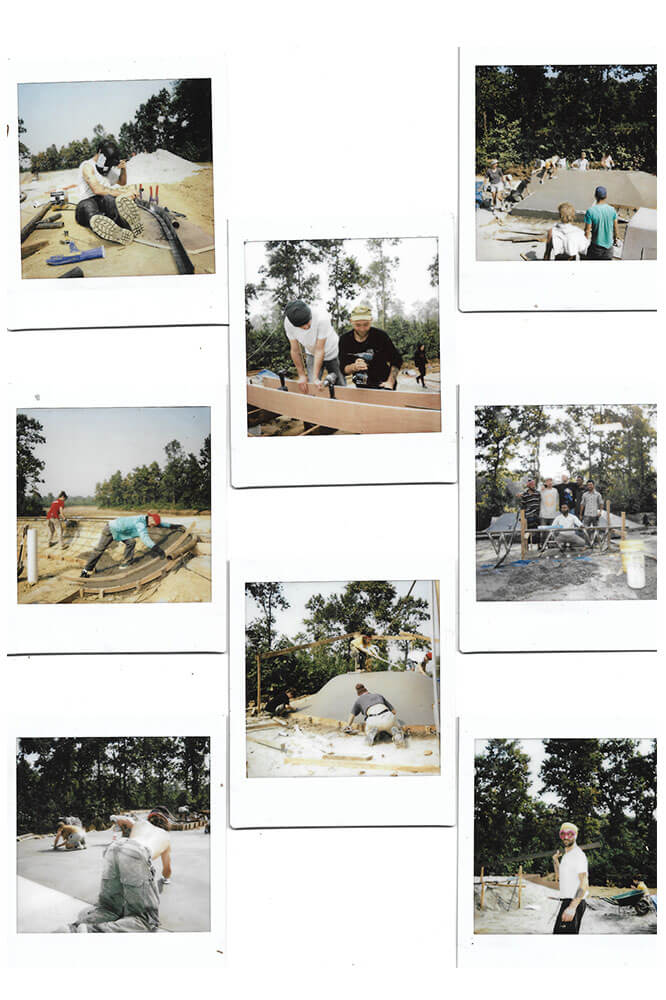

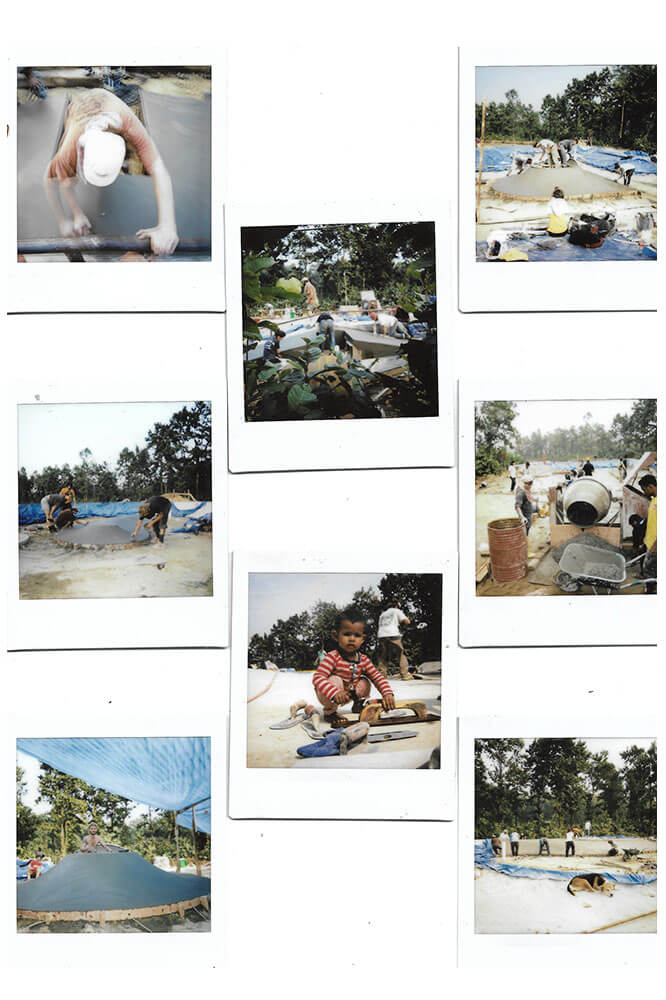

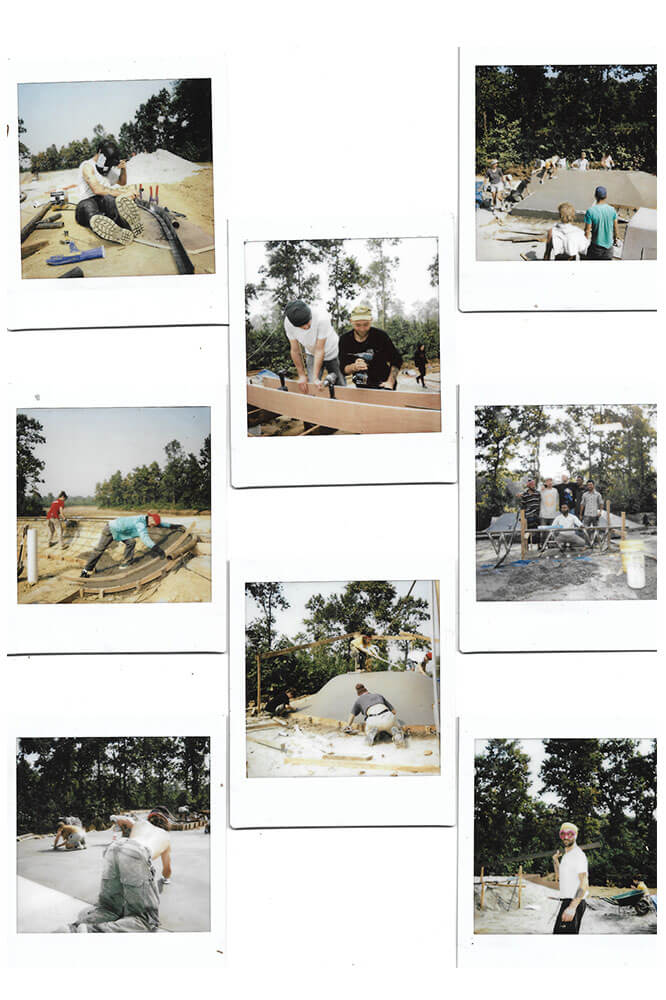

Rising early in the morning the work begins. The dawn chorus sounds. The sun hangs low and red in sky, shining through the trees like the flag itself, dew patters as it falls from the leaves in the forest. Chewy paces the house shrieking the hype-scream like an eagle circling above, cruising on the thermals of the house. “Oh sheet! Here we go ageen!” Chewy has the gift of boundless infectious enthusiasm that is an invaluable quality and a pleasure to be around both on and off a skateboard. The work is tough but much needed. I absolutely love woodwork, but also the heavy stuff, having done some concrete work with some firms in London. But this shit is next level; stepping into a familiar but much amplified and reshaped world. Ratan stands proud at his pounding mixer, face wrapped in a cement dusted scarf, lit cigarette protruding from a small doctored hole, a yellow wellied foot clamping the wheel-operated drum in position while he splashes the mix with water. The work is shovelling, lots of it, wheeling wheelbarrows, pouring, wheeling, pouring, screeding, floating, shovelling, troweling, asking a question, waiting, troweling, waiting, smoking, troweling, asking a few more questions, troweling, talking, troweling. It’s great. I even get a go on a trowel.

Picture by Heidi Facherson

I soon start to get my head into some carpentry, the forming of the pieces. It’s a strange thing to go from my day job of building a structure out of wood and that being the finished item, to building something that is essentially the reverse. Sacrificial carpentry that is ultimately negative space. It requires a shift in thinking, but something I’d love to do a lot more of.

A few weeks later towards the end of the build, I’m already watching some of the guys skate the finished parts of the park. It’s straight in, sweat and slams. I swear with each of Fabi’s pushes, the whole park moves backwards an inch. Dude skates like it’s his last day on earth. I sit and take in my surroundings and dwell on a what needed to happen for Emo and I to get from The Rising Sun in London Bridge to the soon-to-be Royal Bengal skatepark in Gazipur.

Picture by Heidi Facherson

It occurs to me that this site has a unique tone. These people kill themselves for this. They are both driven and mellow, kindhearted and without prejudice, generous with knowledge and tolerant of mistakes. And all for the good of skateboarding, gifting a polished new park to loads of deserving kids in a country where it’s just starting to take hold. I am stoked to have met each and every one of them and call them my friends.

After it all, my previous ideas about mastering concrete as a medium for the purposes of house-builds back home has been completely turned on it’s head. It’s all well and good pouring a nice concrete floor for a paying customer, but you can’t skate a kitchen in Leyton.

Elliott Russell

Picture by Heidi Facherson

Polaroids by Léo Poulet

Polaroids by Elliott Auffray

Picture by Heidi Facherson

Picture by Heidi Facherson

Picture by Heidi Facherson

Picture by Heidi Facherson

Picture by Heidi Facherson

Picture by Heidi Facherson

Picture by Heidi Facherson

Picture by Heidi Facherson

Pictures by Heidi Facherson